Data Collection in Product Testing: Procedures and Reporting

Reliable product decisions start with reliable data. In U.S. product testing, teams collect measurements, observations, and user feedback under controlled conditions so results can be compared across units, test runs, and environments. This article explains practical procedures for gathering data, maintaining quality controls, and reporting findings in a way that supports repeatable evaluation and clear product quality conclusions.

High-quality product testing depends on data that is consistent, traceable, and collected with clear intent. Whether a team is validating durability, safety, usability, or performance, the procedures used to capture readings and observations can influence the outcome as much as the product itself. A solid data-collection plan helps ensure results are repeatable, differences are explainable, and reporting can stand up to review.

How Equipment Testing Is Performed

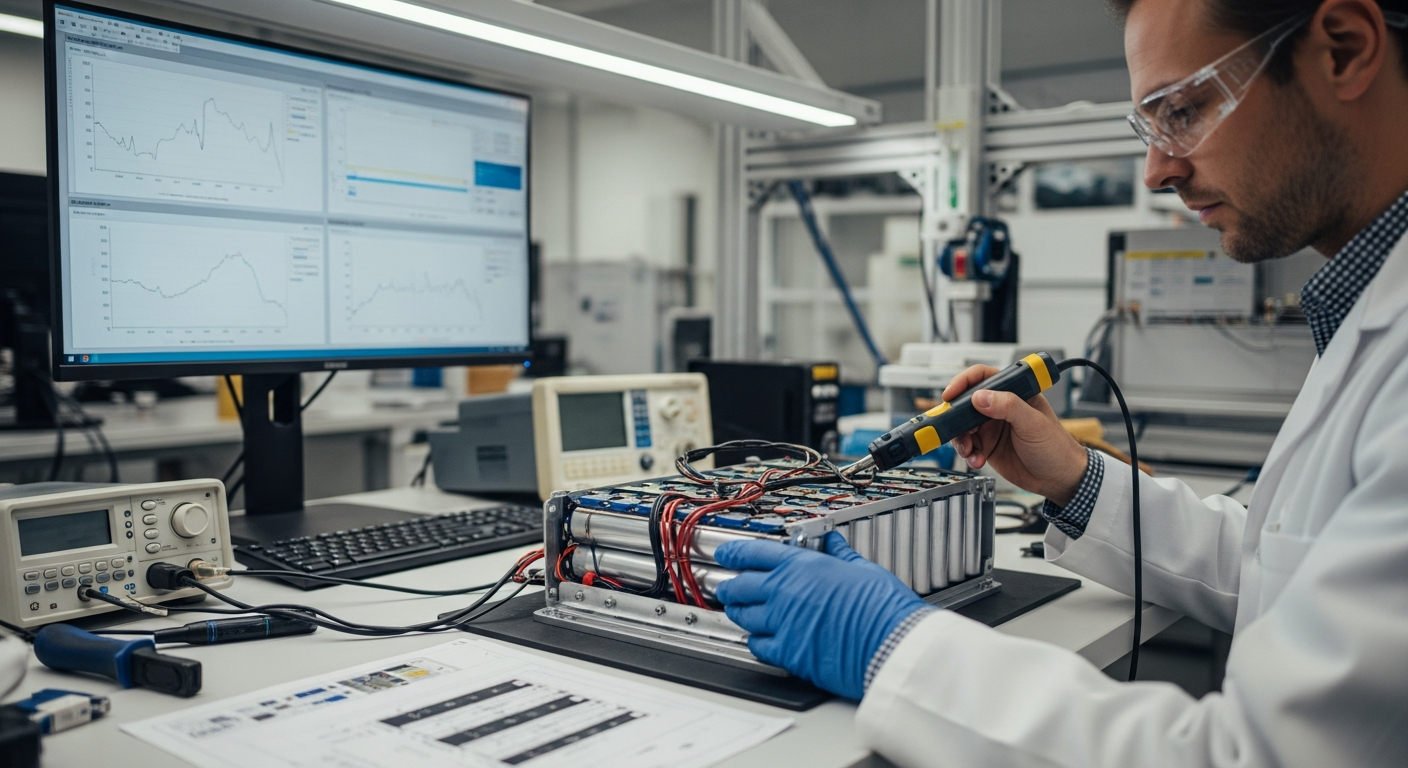

Equipment testing typically begins with a test plan that defines what will be measured, how it will be measured, and what conditions will be used. A practical plan identifies the test objective (for example, verifying temperature stability or impact resistance), the measurement method (sensor type, sampling rate, and calibration approach), and the acceptance criteria. In U.S. lab and field settings, it is common to align procedures with documented internal protocols and recognized standards when applicable.

Data collection works best when the setup is treated as part of the experiment. Test fixtures, mounting orientation, cable routing, and environmental conditions can affect results. For example, vibration readings can change with mounting torque, and thermal readings can vary based on sensor placement and airflow. Good procedures document these details so another team can reproduce the test later.

Instrumentation and calibration are central to trustworthy measurements. Teams typically record instrument model, firmware/software version, calibration status, and measurement uncertainty or tolerance when known. When calibration certificates exist, testers log the certificate date and due date, then verify the instrument is within calibration at the time of testing. If a sensor drifts or a meter saturates, the dataset may still be useful, but only if those limitations are captured in the notes.

Sampling strategy also matters. A one-time reading can miss transient issues, while excessive sampling can create noise and analysis overhead. Teams usually choose a sampling rate that matches the phenomenon being observed (for example, higher frequency for vibration or electrical transients, lower for long thermal soaks). Alongside numeric readings, structured observations are often recorded using checklists to reduce ambiguity, such as visible deformation, audible noise, odor, or user-perceived roughness.

Understanding Equipment and Product Testing Processes

Data collection is not a single step; it is a workflow that runs from preparation through post-test handling. A common approach is to define roles and checkpoints: who sets up the equipment, who verifies configuration, who runs the sequence, and who reviews the data for completeness. This reduces the risk of missing files, mislabeled units, or unclear test conditions.

Traceability is a cornerstone of credible testing. Teams typically assign identifiers to the unit under test, subcomponents, test runs, and data files. For physical samples, this may include serial numbers, lot codes, and build revisions. For software-controlled products, it often includes software version, configuration profiles, and enabled features. Without traceability, a performance shift could be mistakenly attributed to design changes when it actually came from a different build or configuration.

Controls and baselines strengthen interpretation. A baseline run can confirm that the test rig behaves as expected, and a reference unit can help distinguish product variation from measurement variation. Repeat trials support statistical confidence and reveal whether observed differences are stable or random. Even when sample sizes are small, disciplined repetition helps identify outliers that might otherwise be misread as meaningful trends.

Data integrity practices are especially important when multiple people handle the same dataset. Versioning rules, read-only storage for raw files, and a clear separation between raw data and processed data reduce accidental overwrites. Many teams keep an audit trail that notes when files were created, what processing steps were applied, and which scripts or tools were used. This does not need to be complex, but it should be consistent.

Reporting begins during the test, not after. A well-designed test log captures timestamps, step-by-step progress, anomalies, interruptions, and any deviations from the planned procedure. If a connector was reseated, a unit was power-cycled, or an environmental chamber overshot the setpoint, these events should be recorded. Later, those notes often explain unexpected spikes, dropouts, or performance shifts.

Equipment Testing and Product Quality Evaluation

Turning collected data into product quality evaluation requires careful framing. First, results should be linked to requirements or intended use. A measurement is only meaningful in context: a torque value, a battery cycle count, or a response time needs an associated condition and threshold to support a quality conclusion.

A clear reporting structure helps stakeholders interpret outcomes. Many test reports include: scope and objective, test setup and conditions, methods and instruments, sample identification and configuration, results with charts/tables, analysis and discussion, and a summary of findings and limitations. When charts are used, axes, units, and filtering or smoothing methods should be stated so readers understand how the visuals were produced.

Uncertainty and variability deserve explicit attention. Quality evaluation often hinges on whether a result is comfortably inside a limit or close enough that measurement error could change the pass/fail interpretation. When teams cannot quantify uncertainty precisely, they can still report practical indicators such as instrument resolution, repeatability across runs, and observed noise levels. This helps prevent overconfident decisions based on fragile margins.

Anomaly handling is another key part of quality evaluation. If a test produces outliers, teams typically document whether the outlier was traced to setup error, instrument fault, or genuine product behavior. Removing data points without justification can misrepresent performance, while keeping faulty readings without context can distort conclusions. A balanced report explains what was observed, what was investigated, and what decision rules were applied.

Finally, good reporting supports learning. Beyond pass/fail, product quality evaluation often benefits from trend summaries: which conditions were most stressful, which failure modes appeared first, and what design or process factors may be associated with variation. Keeping findings tied to evidence, while clearly stating assumptions and limitations, makes the data useful for future iterations and more reliable decision-making.

Consistent procedures and disciplined reporting turn product testing into a repeatable decision tool rather than a one-off experiment. When data is collected with traceability, calibrated measurement practices, and a documented workflow, quality evaluation becomes clearer, disagreements are easier to resolve, and future testing can build on prior results with confidence.